A Simple Django Web App

Django is a popular web framework for python. Like other web frameworks, the purpose of Django is to help you build websites without the challenge of building everything from scratch. The purpose of this post is to get a minimally, just about useful, app working rather than demonstrating all of what Django is capable of.

The post doesn’t go into too much detail about the theory and explanation for why Django is the way it is. For mor of that I suggest you try the excellent Django Girls tutorial and the Django documentation tutorial.

If you want to get straight to the finished example Django web app you can get it here.

I’m using Django 2.2.16 for this blog post. You’ll need to install it on your own system if you want to follow along.

Create The Django Project

For this example Django web app I have imagined I work for a exciting new start up called ‘Cool Counters Incorporated’ who are working on an exciting new line of web-based counters.

We begin by navigating to our projects folder and running

django-admin startproject cool_counters

Running the startproject command creates a project folder (in this case called cool_counters) as well as a number of other folders and files:

cool_counters/

manage.py

cool_counters/

__init__.py

settings.py

urls.py

wsgi.py

These form the bare minimum needed to make a Django project. At this stage we can actually run it by changing to the cool_counters directory and running:

python manage.py runserver

You can check the resulting page at http://127.0.0.1:8000/ and it should show a placeholder page automatically created by Django.

You will get warnings about ‘unapplied migrations’. A migration is Django terminology for configuring database tables and this warning tells us that migrations are ready but not yet applied. We will see more of this when we create our own database. For now run

python manage.py migrate

which will apply the migrations for the project.

Build The Django Web App

Within the overarching project, Django subdivides areas of related functionality and logic into ‘apps‘. We can create a new app with

python manage.py startapp counter

This will create and populate a ‘counter’ app within the cool_counters project directory package.

In our simple case are only going to have a single ‘app’, but we can imagine that our project might be for ‘Cool Counters incorporated’ and that in future we might make a blog on our web page too. In that case we would probably put the code for the blog in a ‘blog’ app, rather than mixing the functionality. Maybe after our counter app becomes wildly popular we also develop a store app.

cool_counters/

blog

counter

store

To keep this example simple we won’t go into creating a blog or a storefront app. Check out the Django girls tutorial if you want to make a blog app.

If you were to again run:

python manage.py runserver

and check the resulting page at http://127.0.0.1:8000/ you would see that creating the ‘counter’ app hasn’t done anything yet.

Models, Views and Controllers

Django works on the basis of ‘models’, ‘views’ and ‘templates’, which is a variation on the more commonly seen ‘models’, ‘views’ and ‘controllers’.

Models define the data storage of app and are a way of defining a database using pure python.

Views are code which define how the data can be interacted with and other operations.

Templates are the actual ‘web’ part of the web app, which get converted into html to be consumed by a user’s browser.

To build the ‘counter’ Django web app we need to construct and connect each of those different elements. In this blog post I step through more or less a single loop of working with each element.

Template

We are going to begin with a template. In Django terminology a template is html combined with placeholder template tags that will reference deeper parts of the app. When a url is requested by a browser, Django combines the template with the app information to return a complete html page.

The idea is that a designer, unfamiliar with python or Django, could write an html/css template and pass it over to a Django developer to integrate into the django app.

Make a new file in counter/templates/counter called ‘index.html’. There is a convention to have the app name in the templates folder to avoid name clash problems further down the line.

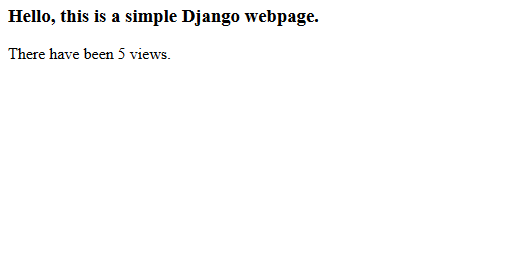

We are going to make a very simple web page which counts how many views of the page there have been.

<h3>Hello, this is a simple Django webpage.</h3>

<p>There have been {{ value }} views.</p>

INSTALLED_APPS = [ 'django.contrib.admin', 'django.contrib.auth', 'django.contrib.contenttypes', 'django.contrib.sessions', 'django.contrib.messages', 'django.contrib.staticfiles', 'counter', ]

Serving that html file with Django isn’t as easy as putting it in a particular place and leaving it at that. We need to do some additional wiring and configuration to

- tell django which url to use for that file and

- provide a ‘view’ for serving up that file. For a small Django app like

Create a URL

To access the index.html file we created, we need to do a bit of wiring work. There are two stages to this: first point the site-wide urls to the counters app and secondly create a url within the counters app.

We start by updating the main, site-wide cool_counters/urls.py (so that urls will be directed to the counter urls.py file which we will create).

This is like saying that our ‘counter’ app is the main app for the site – we don’t want to have to go to ‘http://127.0.0.1:8000/counter’ every time.

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include

urlpatterns = [

path('', include('counter.urls')),

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

]

We now also need to create a urls.py file in the counter app and tell django how to handle a visit to a url.

Into the counter/urls.py file we add the following:

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.index, name='index'),

]

which specifies that navigating to the root of ‘counter’, Django will respond with a view called ‘index’.

Read more about this view in the next section.

View

Views are the way Django bridges the gap between the inner workings of the app and the outside world (typically via urls) see more on views here: .

We have specified in counter/urls.py that when we visit the root level of the page Django should respond by using a view called index. We now need to create that view.

Our index.html template file says that we want to show the value of a counter, and we want that counter to increase each time we visit the page.

To achieve this we need to create a ‘view’ which will interact with a database model. We will read more about models in the next section.

The following view code will create a new entry in the Counter model if it doesn’t exist and increment its value. This code should be in counter/views.py

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from .models import Counter

def index(request):

if len(Counter.objects.filter(key='counter')) == 0:

counter = Counter(key='counter', value=0)

counter.save()

else:

counter = get_object_or_404(Counter, key='counter')

counter.value+=1

counter.save()

context = {'value': counter.value}

return render(request, 'counter/index.html', context)

This code is doing quite a bit, so lets go through it.

First it imports the Counter object from counter/models.py – we will work on the model code next. The function ‘index’ is the view that the urls.py file refers to. In this file the code creates a new counter if one does not already exist and then increments the value in that counter. The value of the counter is passed into the render method as a dictionary known as a context.

Model

The view we made in the previous section referred to a Counter object it expected to find in counter/models.py. We will make this now.

Model in this context refers to ‘data model’ and defines the tables in a database that will be used by the app. You can read more about that concept here. Essentially we want to describe, in python, what will be stored in a database.

Django is capable of interacting with many different types of database, but we will be sticking with the default SQLite database for now.

Let’s define our ‘Counter’ model. It will be a simple table with a ‘key’ field to hold reference to ‘counter’ and a corresponding ‘value’ field.

To do this we go to counter/models.py and add the following to the file:

from django.db import models

# Create your models here.

class Counter(models.Model):

key = models.CharField(default='counter', max_length=10)

value = models.IntegerField(default=0)

To turn this model definition into an actual database table we need to run

python manage.py makemigrations

(which creates sql needed to setup the database)

and

python manage.py migrate

(actually applies the sql to the database)

Test It out

We should now have a working (if rather small) Django app. Fire up the server again with

python manage.py runserver

If you navigate to http://127.0.0.1:8000 on your browser you should now see the html template rendered by Django to also show the number of times you have viewed the page.

Get the project code

The code for this simple Django web app is also available on github:

Check out the readme for full details, but essentially you need to

- clone the repo

- run python manage.py migrate

- run python manage.py runserver

This project is just a toy for getting started with django. If you do want to develop it into your own site, then make sure you change the SECRET_KEY found in settings.py see https://tech.serhatteker.com/post/2020-01/django-create-secret-key/